The Importance of Names and Pronouncing Them Correctly

(Please refer to me as “Kjers” from now on.)

Living in a country with a “foreign” name has its challenges. I've tried to use the humorous nature of how Norway has struggled with my own name to examine the wider issue of why it's important to make an effort to pronounce people's names correctly - both as members of a multilingual society and as language professionals. Hopefully I've succeeded.

What's in a name?

To this day, my Dad still has no idea how he came up with the name “Jessica”. Up until my birth, “Bethany” had been my parents’ first choice, with “Miriam” a close second. But then I'd popped out (in a manner of speaking), and my Dad had taken one look at my tiny, purple face and suddenly thought of “Jessica”.

Whatever he liked about the name, clearly a lot of other people agreed, as it was one of the most popular girls’ names that year. Whenever I, as a moody teenager, bemoaned the commonness of my name, my parents would argue that since I had been born in January, it wasn't their fault that everyone had decided to copy their excellent idea.

However, growing up in the UK with such a name meant that no one ever struggled with its pronunciation or spelling. I didn't even have a problem on trips abroad to Europe: the French merely replace the “J” with a satisfactory “Zh” sound, while the Germans pronounce it as an affirming “Y” sound. I suppose the Spanish may say “Hessica” but I haven't been to Spain yet, so I can't say for certain. I absolutely did not expect to have a problem with my name in Norway, due to the country's renowned English ability and wide exposure to English-language books, films and music. And yet, Norway does struggle with my name - in a way that no other European country has done.

I want to make it clear that this isn't just pronouncing the “J” as a “Y”, as other Germanic countries might. Norway's struggle with my name seems to be two-fold:

Struggle 1: Expectation vs. reality

I remember walking into a Pink Fish cafe after a late-night cinema trip. I ordered my meal in Norwegian and the man behind the till asked for my name.

“Jess,” I said in my English accent. I saw the guy freeze for a split second before typing something on his screen.

“Got it,” he said, confidently, nodding. I returned to my partner.

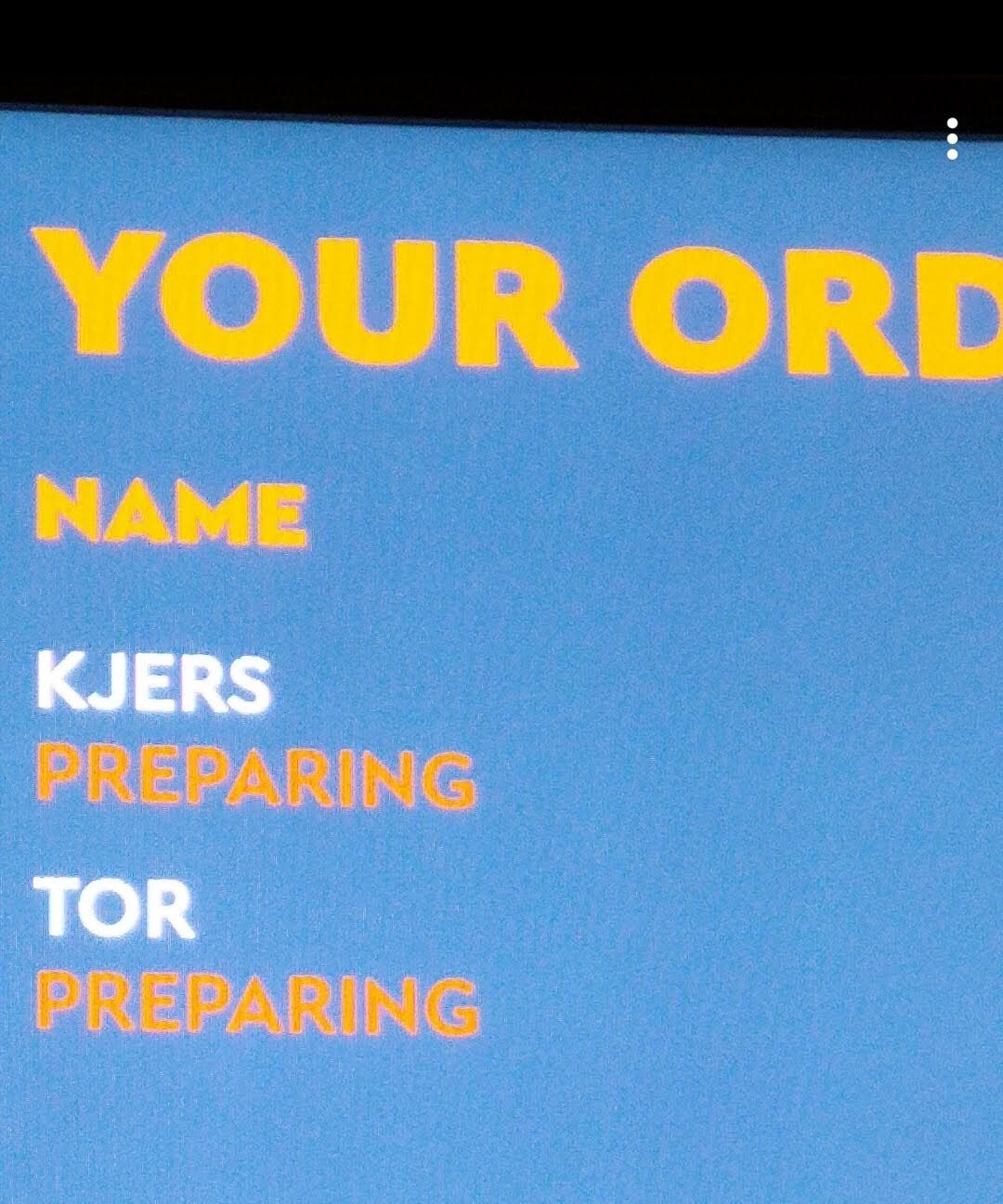

“He absolutely hasn't got it,” I said. Whatever I was expecting though, I was not prepared for what eventually flashed up on the screen: a picture of a pending orders screen that shows “Kjers” instead of “Jess”.

To make the feat more impressive, “Kjers” isn't even a name in Norwegian. Maybe he thought it was an abbreviated form of “Kjersti” (the Scandinavian equivalent of “Kirsty”)? Or maybe he thought that “Kjers” was an old family name passed down due to obligation and a desire to teach me that life isn't fair from a young age?

While I have only been mistaken for Kjers once, I still see the same pause in most Norwegians when I greet them and tell them my name. It may well be that, having had a conversation with me in Norwegian, “Jess” is just not a name they're expecting to hear, and I have noticed a vast improvement in the reception (and spelling) of my name since I've started pronouncing it as “Yessika” (although I should mention that no barista in Finland has ever struggled with “Jess”, so props to you Finland!).

Struggle 2: To nick-name or not to nick-name?

Like many people in the UK, I shorten my name. This probably creates an added layer of difficulty for Norwegians as “Jessica” is a lot more identifiable than “Jess”. However, I've gone by “Jess” for so long that I have a far greater connection to it than “Jessica”, which is reserved for professional settings and for when I've annoyed my parents. However, in Norway, using a shortened or adjusted form of your name as a nickname is relatively uncommon. Therefore, when I introduce myself as “Jess”, a lot of people assume that that's my full, actual, stamped-on-my-birth-certificate-to-be-engraved-on-my-tombstone name.

For example, my Norwegian partner and I were friends before we got together as a couple. A few weeks into our friendship, he found out that my full name was indeed “Jessica”. Having solely known and referred to me as “Jess” up to this point, you can imagine my surprise when I walked into the room one day and he greeted me with “Hei Jessica!". He was firmly corrected and has since been one of the most formidable forces in my life when it comes to explaining my name dynamic to other Norwegians - much to the bemusement of his family.

(However, he remains unconvinced by nicknames such as “Charlie” or “Lottie” for “Charlotte” because “they're just as long as the original!").

A luxury problem?

In Norwegian, the term “first world problem” is translated as “luksusproblem”, which literally means “luxury problem”. I realise that the two problems I've discussed above can absolutely be described in this way, and are more examples of the cultural differences between Norway and the UK surrounding name conventions than actual problems that have had a significant effect on my life and well-being. The people in Norway who I love and who love me call me “Jess” just as people in the UK do, and god knows that people in the service industry have enough to deal with, without me demanding that they scribble my name correctly on a paper cup that's ultimately destined for the recycling bin.

However, the mild irritation I feel at having to adjust my name in daily life can only be minimal compared to the frustrations of people who have names that are even more unfamiliar to Norwegians and have to deal with constant reminders of their “foreignness” or “otherness” - even if they were born in Norway.

Names are important. Whether it's a name given to you by your parents or a name chosen by yourself, it's a part of who you are. At best, someone mispronouncing your name is frustrating. At worst, it can make people feel inferior, not included or disrespected. At the very, very worst, it can reflect xenophobic societal attitudes and contribute to real-world consequences, such as being unable to find work.

I don't wish to give the impression that this is solely a Norwegian problem either - I'd be pleasantly surprised to find a country that it doesn't happen in. American politician Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was incorrectly called “Anastasio” by Fox News and then mocked for “doing the Latina thing” when she pronounced her name with a Spanish accent. Considering AOC's name is a Latinx name, the Spanish pronunciation is the correct pronunciation.

Siri, show me the brand of ‘economic anxiety’ that mocks Americans of color as unintelligent + unskilled, while *also* mocking those same Americans for speaking more languages than you: pic.twitter.com/HXBC7Osexu

— Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (@AOC) March 21, 2019

I think I always knew the importance of pronouncing names correctly - I remember one of my best friends sitting me down at eighteen and drilling my pronunciation of her Welsh name. However, I don't think I truly understood the implications of the issue until I came to Norway and experienced that frustration as a person with a name considered unusual by the majority population - even on a minor scale.

As members of an increasingly multicultural and multilingual society, it is important that we all make an effort to pronounce people's names correctly. As language professionals, be it translators, linguists, teachers, etc., it is even more important, not just as a sign of professionalism and respect for our clients, but as evidence of our own understanding that language, culture and identity are inextricably linked and interwoven.

And if you ever meet anyone named “Kjers” wandering around Oslo, I would appreciate it if you apologised to them on my behalf for taking their Pink Fish order!

Originally posted to LinkedIn on 9 December 2019.